Maybe it’s a cousin with his first short story. Your quiet aunt who finally finished her draft of a romance novel. Your college roommate with a manuscript about aliens. Whatever the case, giving feedback can be as intimidating as receiving it. After a decade-plus of practice giving and receiving feedback, I’ve found the following rules of thumb work well for me.

Be precise.

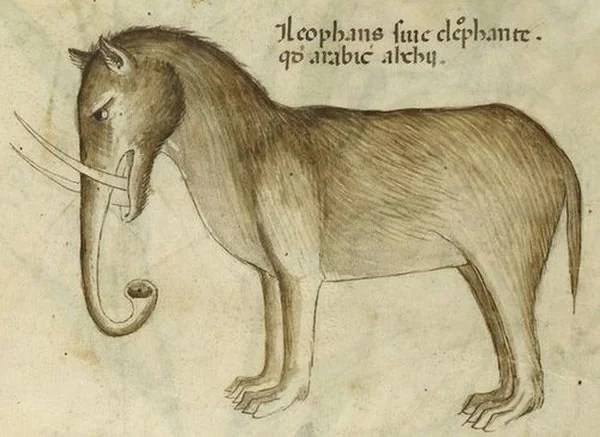

Ever seen medieval attempts at drawing an elephant? Imagine your artist buddy comes to you for feedback. He’s sincere about wanting to improve, and you want to be helpful. You want to see him grow and flourish in this new skill. So, after you do or do not have a small giggle in private, you have some options for how to respond.

You could hand it back and say, “I dunno. It doesn’t make sense.” Shrug and say, “I didn’t really get it. Sorry.”

But what can your friend do with that? First off, those responses are hurtful (because it seems like you can’t be arsed to really consider this attempt). Second, those responses are uselessly vague. Instead, identify a place to start. Specifically . . .

Target the BIG issues.

Try to identify the two to four biggest problems that really caused you to stumble. What were the worst speed bumps for you as a reader? A main character’s backstory or lack thereof. World building as a whole. Lack of tension. Too many side characters that distract from the main plot. A shift in the characters’ goals that didn’t feel right. Points where the momentum breaks or a twist is jarring versus surprising.

You don’t need to catalogue every issue. Just try to identify which part of their “elephant” threw you off the most.

Fixing one problem will often lead to correcting another: If your friend fixes his elephant’s oversized eye, he’s likely to tweak the jawline too. Plus refining a piece is a process: Your job isn’t to get your friend to a perfect elephant, just to offer a few suggestions aimed at something more elephant-shaped. You’re helping them find their way toward the next draft, not necessarily the final draft.

Then, and here’s the trick, leave space for your friend to do their own research and make their own creative decisions.

Trust the writer to fix it. Don’t confuse “be precise” with “fixing the problem for the writer.”

Painting an elephant is your friend’s passionate undertaking—not yours. In terms of phrasing, think “your elephant’s skin texture seems off to me” versus three paragraphs on what elephant skin has to look like. Your friend needs (and should want) to decide that. And who knows what they’ll come up with? Your friend might redraw the elephant at dawn (in orange light) or at dusk (in purple light), or maybe the elephant will be wet or covered in dust, evoking colors and textures you never considered.

If you’re struggling to trust the writer, make sure you’ve taken time to . . .

Note your favorite positives.

Yes, it’s true, writers have feelings. Writing is really hard, and sharing writing can be really scary, and a lot of societal forces work to make us feel small and stupid for any creative expression that’s not immediately monetizable. But in addition to that, in a functional, practical sense, identifying positives is constructive.

Authors don’t need to master all writing skills to tell fantastic stories.

I said what I said.

Readers are diverse. They read for different things. Kick-ass pacing? Who cares about flat characters. Stunning lyrical language? That fuzzy world building is whatever. It’s helpful—part of self-discovery as an artist—to recognize what areas of writing you love and are already doing well.

It’s incredibly rare (impossible, even?) that somebody gets something so wrong you can’t find a single point of potential, not a single reasonable foundation on which to build.

To that effect:

Always have a mindset of progress and growth.

It’s okay that what you’re reading isn’t at the level of “professional finished book” just yet—that takes a village. You’ve been trusted with an invitation to join that village. Try to be a respectful member.

Approach feedback with the genuine belief that the person wants to improve—believe, in your heart of hearts, that they can. Strive to fold that belief into the phrasing of your feedback.

And if you can’t manage any of the above . . .

Know when to say “no.”

Sometimes the kindest, most helpful thing you can do for a writer is to decline to offer feedback on their work.

If you don’t have time to be precise, identify the big bumps, or note the positives, then you don’t have time to give feedback. And that is okay. That’s perfectly okay! Guard your time.

If your friend is writing epic fantasy, and you only read memoir, be very clear about that. There’s a lot to learn from critique partners who excel in different genres . . . but in a broad sense, you can’t help somebody shape their elephant if you’ve never seen an elephant! Finding readers familiar with our genres is crucial.

And finally . . .

Be brave. Stay humble.

One fear I hear a lot from people new to giving feedback is that, if anything goes in art, how can they say for sure that something is “wrong?”

Here’s the thing: People are different, which means readers are different. My profound disappointment that This Is How You Lose A Time War only has a 3.87 on GoodReads is clear evidence. Take this diversity among readers as liberating, a relief: it means that, in feedback, you are a valid reader. You are somebody’s target audience.

Part of a writer’s journey is finding their target readers. Worst-case scenario, even if your feedback ends up not being a good fit for the writer, that is still helpful. A tough but important lesson of writing (and putting your writing out there) is that not everybody will love it. You’ve agreed to be an honest reader for your friend, that’s all. Enjoy getting to be a small part of somebody’s creative journey!